I have firsthand experience at how devastating an invasive insect called the emerald ash borer can be. Small it may be; inconsequential it is not.

If you don’t have ash trees, who some say are headed to “functional extinction” because of the emerald ash borer, you might not know the extent of the problem.

A tiny insect called EAB

EAB, as the insect is called for short, has killed millions upon millions of ash trees in at least 36 states. It is also ravaging trees in Canada.

Millions of ash trees dead; millions more at risk

While the total magnitude of the ash trees killed is hard to know, the North Carolina Forest Service said it rivals what happened to hemlocks (affected by hemlock woolly adelgid) and American chestnuts (affected by chestnut blight) in the early 20th Century.

In Tennessee alone, there are (or recently were) 271 million ash trees with an estimated worth of $11 billion.

The emerald ash borer is a small beetle native to China, Japan, North and South Korea, Taiwan, Mongolia and areas in eastern Russia.

The emerald ash borer been called the most destructive insect to ever invade the United States.

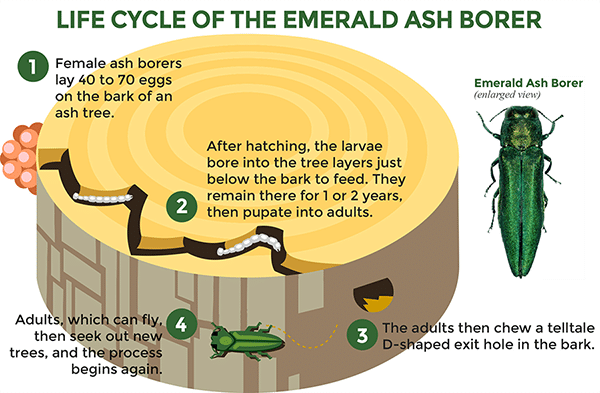

How ash trees are damaged

“EAB larvae kill ash trees by tunneling under the bark and feeding on the part of the tree that moves water and sugars up and down the trunk,” according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The beetle is believed to have arrived in the United States in 2002 in Michigan in shipping crates from China built from ash.

By 2010 the insect made its way to Tennessee, discovered at a truck stop on Interstate-40 in Knoxville. That’s a hint on how it spread. While the emerald ash borer can fly surprisingly long distances for such a small insect, humans have helped it spread quicker across hundreds of miles.

The insect has been found in 65 of Tennessee’s 95 counties. Nashville started removing 469 ash trees in October, but has thousands of infested trees. An estimated 20 million ash trees in Tennessee have been lost to the insect in the past decade.

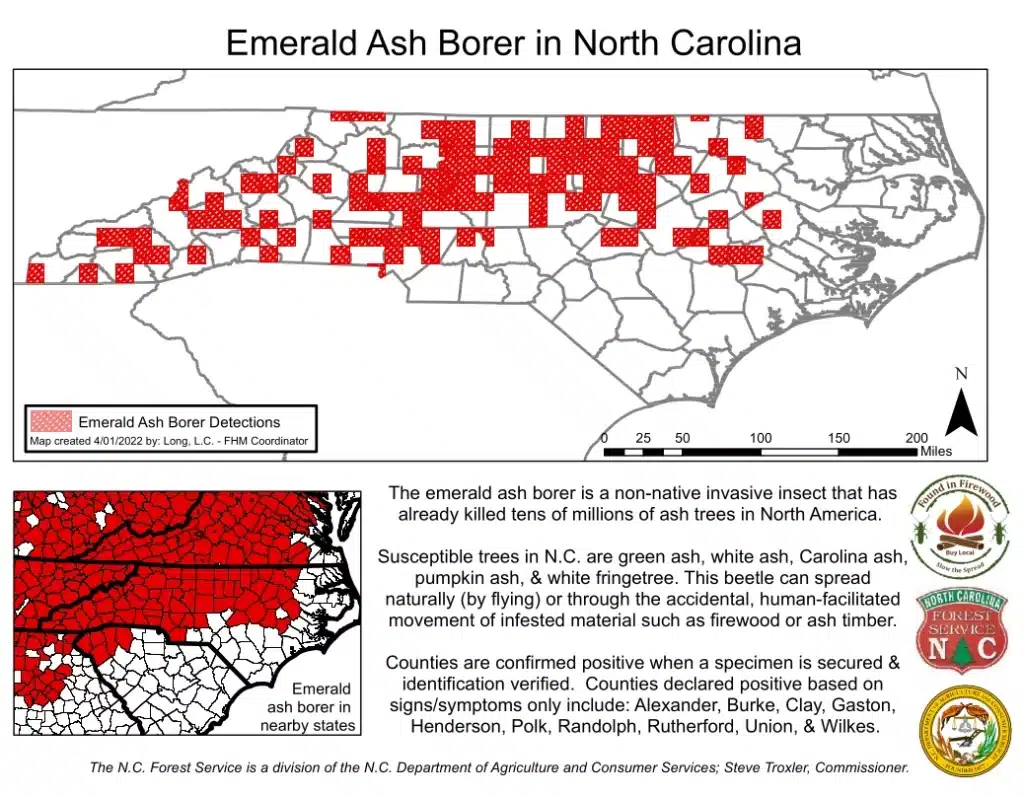

EAB reaches North Carolina

By 2013, EAB reached North Carolina.

EAB was first noticed in Yancey County, North Carolina, where our mountain home is located, in 2016. Not surprisingly, mountainous Yancey County borders Tennessee and is not that far from areas of Virginia where EAB was found around the same time.

By last year, a giant ash tree on our property looked dead (no leaves) and had became dangerously brittle. The crowns of every other ash on the property showed signs of damage (the trees are killed from the top down).

Trees begin to show damage from the beetle in two years and be dead in five. There is not much that can slow or stop the destruction although chemical treatment is option that works in some situations.

Fighting back with stingless wasps

Biocontrol, with the introduction of stingless wasps about the size of mosquitoes from China and Russia, may be the best hope. The wasps target emerald ash borers. The wasps will reduce, not eliminate, the population of emerald ash borers.

Firewood quarantines and other restrictions on the movement of live trees and lumber have not worked, but restrictions remain in place in many states.

The Department of Agriculture lifted its restrictions on live ash and borer-invested wood in 2021 after spending over $350 million in the effort to save ash trees over the last 20 years. The department is now focused on biocontrol and other research .

Our removal of dead or damaged ash trees

Isak Pertee and his crew at High Lonesome Timber in Burnsville, North Carolina, removed infested ash trees on our property in November and December of last year.

Because a couple of the trees were very large, close to the house and far from the street, it was a complex project that involved cutting and lowering sections of the trees, using a crane and using a special “spider lift.”